THE SCIENCE OF SOIL: IT’S NOT DIRT!

Published 12:00 am Monday, October 24, 2005

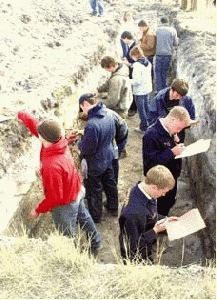

- FFA MEMBERS participating in the state soil judging contest study the horizons at one of three test sites. (Story and photos by Mardi Ford).

From Klamath Falls to Clackamas, more than 200 kids from FFA chapters representing 27 high schools from all over the great state of Oregon came here last week.

Trending

For many, it was the first time they’d visited the Grande Ronde Valley.

By 9, they were standing silent in the crisp October morning clipboards and pencils in hand. With rapt attention they focused on Matthew Fillmore, a soil scientist with the Natural Resource Conservation Service in Tangent.

He was revealing the results of the soils practice test they had just taken at the Eastern Oregon Livestock Show grounds in Union.

Trending

For the past hour, each of these kids had taken their turn at studying the layers or horizons revealed across the sides of a long earthen laboratory. This 7-foot deep, 5-foot wide, 30-foot long pit was excavated strictly for this purpose.

Who would have thought dirt could keep 200 teenagers so quiet, for so long?

"It’s soil. Dirt’s what’s under your fingernails," says Rob Horn.

Horn, the retired FFA advisor from Oakland, Ore., has participated in this event since the 1970s. This year he’s here to help with the scoring and root for Oakland.

Horn says soil judging is a mixture of mathematics, science, common sense and an understanding of what makes up the landscape we live in.

"When I used to teach, I’d take my kids on a three-day geology trip. I wanted them to understand where the soil came from the wind, water, volcanic activity and whatever else that formed the landscape also brought in specific materials that are still part of the soil."

After the practice results have been checked, students are divided into three groups and board school buses bound for one of three other sites located throughout the valley. At each site, the students will be looking at and gauging a variety of things within each specific horizon including soil color, texture, structure, moisture and something called mottles, the presence of which reveals rust.

Once they describe what they see, contestants must interpret their findings and determine such things as effective depth of the soil, available water holding capacity, surface permeability, water and wind erosion hazards.

They will also describe characteristics of each landscape What is the slope? Are there a lot of rocks? If so, are they smooth and round like and old river bed, or rough and porous like volcanic material? Is alluvium stream-deposited material present? If so, is it recent or is it ancient?

All of these descriptions and determinations lead to the final category of interpreting those determinations as to suggested management of water, crop suitability, erosion and more.

And they have 45 minutes to do it all.

For a lot of these kids, the contest is admittedly a day off from being cooped up inside a classroom and a possible overnight trip to someplace different.

But it’s also exciting, says Lena McClelland from Cove. This is the first year at a soil judging contest for the junior from Cove High School. The chapter is new this year and, McClelland admits, so is soil science.

"We’re behind, but we’re learning. Our adviser (Toby Koehn) told us to have a good time and not worry so much about the competing this year. Next year, we’ll know what to expect. It’s interesting. I never really thought about (soil) before, but it’s fun," she says enthusiastically.

For others, the contest is an opportunity to test their math and science skills. Braden Bair, a senior from Nyssa High School, took first at his district’s soil judging contest.

Growing up on the family farm, soil is something he has studied all his life and says the contest requires a good understanding of math and science. Though he plans to pursue science and math in college, by going into medicine, he gives credit to a firm foundation in the land.

"Agriculture is the basis for everything in the world," he says simply.

Nearby, Danielle Simpson says she plans to study agri/business in college and admits the district contest is a chance to make the national competition and learn even more.

She agrees wholeheartedly with Bair’s assessment of the value of agriculture.

"Without agriculture, there’d be a whole lot of stuff we wouldn’t have like food."

But, whether the other FFA members pursue agriculture, like Simpson, or medicine, like Bair, the lessons learned in the soil of the Grande Ronde Valley will help prepare the way.