Exhibit details culture, history of nine tribes

Published 8:30 am Friday, October 1, 2010

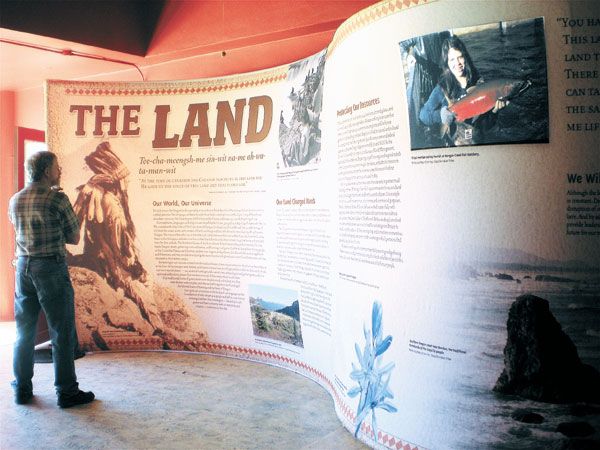

- JOYCE OSTERLOH photos Visitors to the Oregon is Indian Country exhibit in Enterprise see a presentation by the nine federally recognized tribes of Oregon and the Oregon Historical Society never before compiled in one exhibit.

ENTERPRISE – For many people, the image of the American Indian is frozen

Trending

in a romanticized past conjured from the “Lone Ranger” TV show or old

Western movies.

The Oregon Historical Society’s traveling exhibit called “Oregon is

Trending

Indian Country,” now on view at Stage One, 117 1/2 Main St. in

Enterprise, will change that perception.

Made up of three large panels each with a separate theme, the project brings all nine of Oregon’s federally recognized tribes together with the Oregon Historical Society to present information on contemporary indigenous cultures never before assembled in one exhibit, according to the historical society’s website.

Each panel display explores one of three themes from the perspective of Oregon’s nine tribes: the land, federal Indian policies and tradition. The land panel explores the Native Americans’ connection to place and the importance of the earth to their survival and spirituality.

Tribal forms of government rooted in the land had emerged before the United States and Oregon even existed. The exhibit points out that when the demand for land and resources grew with the onslaught of European emigrants and the competition became violent, the Indians were forced from their homelands. Sixty million acres in Oregon passed out of Indian hands.

Today 875,000 acres, or 1.4 percent, remains under tribal ownership. Every Oregon tribe, the exhibit shows, is involved with state and federal agencies such as the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, the Bonneville Power Administration, Bureau of Land Management and the U.S. Forest Service to ensure resources that nourished Native Americans long ago still sustain the inhabitants of the land today.

The panel titled “Federal Indian Policies” is, in the opinion of Rich Wandschneider, director of the Alvin and Betty Josephy Library of Western History and Culture at Fishtrap, the most educational of the three displays. Wandscheider said he learned more from that panel than the others as it succinctly compiled more than 150 years of U.S. and Oregon government policy decisions and how they affected the tribes in both negative and positive ways.

The panel begins with the Oregon Treaty Commission, which was created in June 1850 to negotiate with the tribes of Western Oregon for title to their lands. Three months later, before negotiations had even begun, it shows, the Oregon Donation Land Act authorized distribution of Indian lands to emigrants. Between 1850 and 1855, 7,437 settlers acquired 3 million acres of Indian land in Oregon.

Treaties between 1853 and ’55 guaranteed rights of access to “usual and accustomed stations” in the ceded Indian lands to hunt, fish and gather food to the Umatilla, Warm Springs and Klamath tribes that the Western Oregon treaties did not. These treaties, formal contracts between sovereign nations, were the first official treaties in the Pacific Northwest.

In 1877 the Dawes Act divided tribal lands into parcels for private ownership, the panel explains. Land fraud was rampant and within a few years individuals had lost their land to non-Indian holders.

John Collier, federal commissioner for Indian affairs in 1934, encouraged passage of the Indian Reorganization Act, which enabled Indians to form modern governments with constitutions for their tribes. Implementation of the act moved slowly and was embraced doubtfully by Native American people who had been misled by many supposed beneficial policies in their dealings with the state and federal governments.

Yet another shift in federal policy occurred in 1954. It is referred to in the exhibit presentation as the “Termination Era” and was intended to liquidate tribal land ownership and move Indians to “mainstream society.” It incidentally opened the Klamath Reservation to logging companies. Indians were encouraged to move to the cities and be retrained to enter the workforce.

Congress terminated every band and tribe in Western Oregon; 109 tribes were terminated nationwide between 1954 and 1961; 62 in Oregon alone, the most of any state in the nation.

The Umatilla and the Warm Springs tribes were left intact. This movement represented the decisive breaking of all treaties and made possible the final colonization of Indian lands.

By the 1970s Indian activism in protest of this treatment had risen to a level that necessitated another change in federal policy for Native Americans. Then-president Richard Nixon introduced a new direction called the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act in 1975. It allowed tribal participation in policymaking in many areas of Indian society.

Between 1972 and 1989 the Burns Paiute Tribe, the Confederated Tribes of Siletz, Cow Creek, Confederated Tribes of the Grande Ronde, Coos, Lower Umpqua, Siuslaw, Klamath and Coquille were restored. Some were granted reservation lands that had been dissolved or sold. This meant that tribes could begin rebuilding their communities and managing their lands and resources, a process that is ongoing today.

The product of this restoration process is shown on the panel titled “Traditions That Bind: the cultural traditions that continue to nurture us.” This panel stresses the importance of reviving and preserving the many tribal languages that were all but eliminated throughout the 19th to mid-20th century.

Language is now recognized as an important resource in relating culture and history to land and place. More than 25 tribal languages and dialects were once spoken in the area known as Oregon. These languages demonstrated the diversity of the tribes and identified them as distinct sovereign nations, the exhibit shows. When the reservations were formed, it was not unusual to hear several different languages all in one place, including the Chinuk Wawa, the trade jargon that became the common language of the community.

This panel explains that all nine of the recognized Oregon tribes sponsor Culture Camps where for two weeks young tribal members receive language instruction. In addition, they participate in cultural activities such as basket weaving and the gathering of materials to make baskets. They make drums, carve canoes, learn flint knapping and tool making. Their history and language classes include trips to places of historical and cultural significance.

The exhibit also showcases the charter schools of the Umatilla and Confederated Tribes of Siletz. The students are immersed in their culture in addition to mainstream subject instruction. Language immersion is a part of the curriculum to teach Chinuk Wawa to preschool and elementary children.

On Sept. 23, Tom and Woesha Hampson presented a lecture called “Culture and Continuity in Indian Country” as part of the programming scheduled around the traveling exhibit on display in Enterprise.

Woesha Hampson is a writer and an educator. She is the granddaughter of Henry Roe Cloud, the first Indian admitted to Yale who was eventually appointed superintendent of the Umatilla Indian Agency and regional representative for the Grand Ronde and Siletz Indian Agencies in Oregon.

Tom and Woesha lived and worked on the Umatilla Reservation in the 1970s. Woesha used a reading of a family history narrative poem to shed light on some of the controversial issues her grandfather had faced. He had supported the Indian Reorganization Act because it had offered loans and other support for higher education of Native Americans. He felt strongly that in order for Indians to be leaders, they must be educated at the college level. He established the first all-Indian college prep school.

Henry Roe Cloud had embraced Christianity and believed it to be a strong spiritual foundation for Native Americans. He was seen as having become part of the non-Indian way of life, but, Woesha stressed, he had worked all his life to preserve the Native American traditions and culture whenever possible. Many of his descendants are involved in improving opportunities for Indian people.

Tom Hampson is director of the Oregon Native American Business and Entrepreneurial Network. He was asked by the Umatilla Tribes to help write the text for the exhibits at the Tamastslikt Institute and contributed to the creation of the dramatic production “The Ghosts of Celilo.”

Tom spoke of the importance of achieving the balance between economic development and cultural preservation created by the emergence of the Native American gaming industry. He said economic development would further cultural revitalization and said Antone Minthorn, a spokesman for the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla, believed the second coming of the Indians might look different than we imagine. It might include casinos, truck stops, cultural institutes and language revival programs. He said, “Coyote was a shape shifter and could appear in many ways.”

The “Oregon is Indian Country” exhibit will be on display at Stage One through Oct. 6, Tuesday through Friday from 11:30 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. On Oct. 6 at 7:30 p.m. David Lewis, Ph.D, will present “Treaties and Sovereignty in Indian Country.” Lewis is the manager of the Cultural Resources Department for the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde.

Even though the exhibit will no longer be available, a lecture and presentation on “First Foods in Indian Country” by Joe McCormack and Eric Quaempts is scheduled at the Fishtrap house on Grant Street in Enterprise on Oct. 20 at 7:30 p.m. McCormack works for the Nez Perce Fisheries in Wallowa County and is hunter, fisherman and student of his tribe. Quaempts is the director of the Department of Natural Resources for the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation.

To make arrangements for schools and other groups to view the “Oregon is Indian Country” exhibit, call Fishtrap at 541-426-3623.