Prized pork

Published 9:59 am Thursday, May 2, 2013

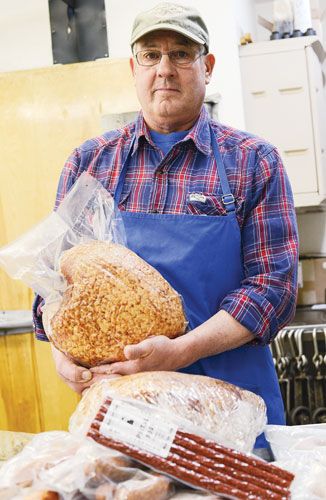

- Howard Elmer, of Pigtail Pork in Cove, holds a specialty ham that he entered at a meat competition in Helena, Mont., on April 26. (Kelly Black photo)

Peppered bacon earns Pigtail Pork accolades at Northwest Meat Processors Association show

by Kelly Black/For The Observer

Howard Elmer, owner of Pigtail Pork in Cove, won the coveted best in show award for his peppered bacon at the Northwest Meat Processors Association show in Moscow, Idaho, on April 6.

Elmer won grand champion for specialty bacon and then competed against 19 others, who had also won grand champion in their respective category, to win the award for best overall product at the show. He also won a grand champion award for his dry-cured Italian sausage. The fennel-infused, dry-cured sausage was never cooked but took about 50 days to cure.

Elmer is passionate about perfecting his smoking andcuring techniques, but he is somewhat hesitant about all the attention.

“I like to be the best at whatever I am doing, but I don’t like accolades,” said Elmer.

Elmer also competed in another meat show in late April in Helena, Mont. His stainless steel work station is piled with mouth-watering fare: large slabs of bacon, two 20 pound hams, Italian sausages, Canadian bacon, smoked bratwurst, polish sausage, summer sausages and pepperoni snack sticks.

Elmer is inspecting his notebook where he has the ingredient list and cook schedule detailed for each product that will be entered into the show. Most products are not cooked by time, but by internal temperature. Elmer’s computerized smokehouse can be programmed for 100 different recipes with up to 30 stages per recipe.

The recipes call for gradual temperature change. A ham takes about 13 hours to smoke and cook. But if the ham gets hot too quickly, it will harden on the outside and hamper the internal temperature from rising properly.

“Even a cook at home needs to understand that,” said Elmer. “Don’t set your oven at 400 and expect that it will cook faster than if you set it at 300.”

The same is true with cooling things. Cooling a ham at room temperature is more effective than, say, 32 degrees.

“The outside gets extremely cold and now the heat can’t escape,” said Elmer.

Good product takes time. Even the pepperoni snack sticks take about nine hours to cook.

“We’ve made a lot of mistakes,” said Elmer. “We’ve eaten some of it; we’ve let the dogs eat some of it.”

Elmer is a third generation grower. The farm used to raise pigs that were sold to a corporation and shipped to a slaughterhouse. As the cost of transport grew and many growers went out of business, Elmer had to make a decision. About 15 years ago the family decided to build a slaughterhouse, butcher shop and packing facility. Today Elmer, his son, Sage, and their family handle all parts of the business from raising the pigs to getting the pork products into the hands of their customers.

Once the customer was a corporation. Now every customer involves personal interaction. Today people as far away as Portland and Florida are repeat customers.

“Providing the customers with a quality, healthful product is the most satisfying aspect to me,” said Elmer. “And at an affordable price too.”

Angie Shurtleff and Julie Bolling, from Haines, stopped by Elmer’s butcher shop to pick up some pork. They left with their hands full of pepperoni sticks, bratwurst and sausages. Bolling bought one half a pork from Elmer several years back.

“It was wonderful,” said Bolling. “There is no way I’ll ever buy pork from a store anymore.”

Elmer says the secret is in the marbling. He shapes the genetics of his herd to put marbling into the meat. According to Elmer, this is a different approach. Elmer used to compete and win at shows where the evaluation was based on weighing the live pig and then, after butchering, measuring how much bacon or ham it produced.

“What you were after is a breeding line that would produce the most meat,” said Elmer.

After his business model changed from selling to a corporation to processing meat and selling product to individual clients, Elmer began shaping the genetics of his herd toward taste, and marbling.

In fact, Elmer does not sell pigs for 4-H or FFA projects because the judges want to see a more muscular animal.

“Our pigs would not win these fairs and livestock shows,” said Elmer. “They don’t look like Arnold

Schwarzenegger.”

Pigs with accentuated muscle do not taste as good, according to Elmer. He is concerned that some of the judges at the shows have led young people who are learning how to raise pigs down the wrong path.

Elmer hosted two meat-cutting demonstrations for local 4-H groups last year.

“The room was crowded with kids and adults,” said Elmer, “so I get on my soap box and tell them, ‘What you guys are raising I wouldn’t eat.’ “

The 4-H students inspected his cuts of meat and then they talked about marbling.

Elmer’s barns have pigs from Duroc, Berkshire and Yorkshire lines. The animals are raised without stimulants or hormones and eat grain grown on Elmer’s farm. He sells half or whole pigs and there is usually a waiting list.

The wall in Elmer’s butcher shop is lined with award plaques from various meat competitions. His first show was in Pendleton in 2006. He won reserve champion for bacon and fresh sausage. The newest plaque is shiny black with gold trim. It reads Northwest Cured Meat Championships: Best Overall Product.