The spawn is on at Wallowa Lake

Published 11:31 am Friday, September 27, 2013

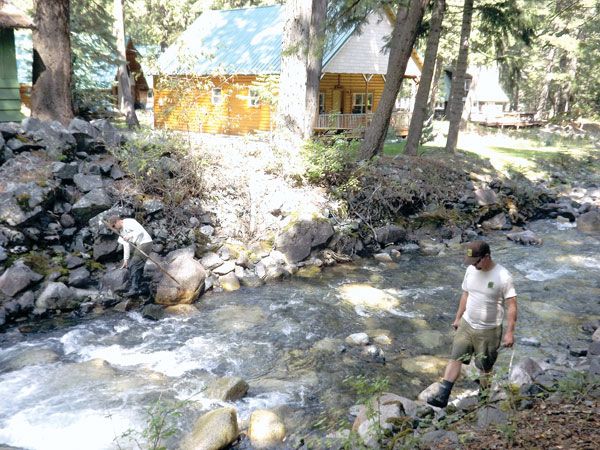

- Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife biologists Jeff Yanke and Kyle Bratcher count kokanee in the west fork of the Wallowa River as part of Pacificorps Wallowa Falls dam reclicensing process. (Katy Nesbitt/The Observer)

ODFW fish biologists are counting thousands of kokanee in few-mile stretch

WALLOWA LAKE – A regular part of the ebb and flow of a Wallowa County fish biologist’s year are spawning ground surveys.

This fall, a different species was added to the list – kokanee in the upper reaches of the Wallowa River.

Kokanee are land-locked salmon, related to the sockeye, which head to the ocean for part of their life span.

Because of the Wallowa Lake dam, the kokanee stay in the six mile, 302-foot deep lake their entire life. That is, until they go up the west and east forks of the Wallowa River to spawn in the late summer and early fall.

A few years ago, record-sized kokanee were being yanked out of Wallowa Lake one after another. In the last couple years, the large fish are gone, but the overall numbers are incredible – last year, 996,000 were estimated to be living in Wallowa Lake, according to Jeff Yanke, Enterprise district biologist for Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. This year’s estimates could easily top 1 million.

Typically the kokanee are counted using hydro acoustics, or a “fancy depth sounder,” which uses sonar to count fish underneath a beam on a boat.

But this year Yanke and Kyle Bratcher, assistant fish biologist for the district, are helping count thousands of fish in a few mile reach from the lake to the tail race of the Pacificorp dam as it renews its license with federal and state agencies.

“The premise is that Pacificorps’ hyrdo plant at Wallowa Falls, through its relicensing process, is considering rerouting the tail race (water coming out of the dam) from the west fork to the east fork,” Yanke said. “By taking water from the west fork and putting it in the east fork, how many kokanee will that affect? We are trying to determine the impacts.”

The intention of the survey is to find out how the potential of dewatering a short stretch of the river will affect kokanee spawning grounds as well as those of bull trout, an endangered species.

The state has volunteered to do a survey every other week until mid-October, Yanke said. Pacificorp will do some of them, and biologists from U.S. Fish and Wildlife have volunteered as well.

Yanke and Bratcher headed out for their first count the beginning of the third week of September, perhaps a week or two ahead of the peak spawn.

They started at the mouth of the Wallowa River where its braids spill into the lake.

Compared to a 33-inch chinook or steelhead, counting kokanee is a whole different ball game. The average size of the spawners this year are between 6 and 12 inches.

This early, there weren’t a lot of carcasses, but enough to attract a bear cub to pick one up and gnaw on it as the fish biologists made their way past BC Creek, a tributary to the west fork of the river.

Yanke and Bratcher aren’t “working up” carcasses on this survey as they would for chinook or steelhead – checking to see if they’ve spawned and collecting data samples.

This work entails counting thousands of fish, sometimes by ones and twos and other times estimating in large pools that hold 1,000 to 2,000 kokanee.

The biologists are also counting redds, or fish nests, also a bit of a challenge with this species since the fish tend to spawn on top of each other, Yanke said.

Yanke said the spawn size of the kokanee changes from year to year.

“The fish have an interesting choice. They risk mortality from starvation by growing bigger or spawn at a smaller size.”

A bigger fish produces more eggs than a smaller fish – increasing their ability for greater abundance, Yanke said.

As Bratcher wove his way through the half dozen braids at the mouth of the river, penciling in numbers by the 10s and 20s he said, “This is about as hard as it gets counting something.”

Lindsey Jones with Wallowa State Park has partnered with Fish and Wildlife to get the word out to lake visitors about the fragility of the fish easily seen along the braids and from the bridges that cross the river.

Yanke said that signs have been put up around the park about the spawning season and volunteers encourage people to be careful around the nesting grounds.

The eggs are released in fine gravel, carefully cleaned off by the female, and they incubate until February or March, Yanke said. When they hatch, they feed off their yolk sack before they venture out as a very small fry.

At Boy Scout Falls, the end of the survey, the biggest of the kokanee congregate in a good-size pool.

Bratcher said it may be because they are stronger than the smaller fish and can make the trek up through faster water, sometimes jumping over small log jams.

Bratcher said when he was a natural resources student at Oregon State they would say, “Working a fish is like working on trees, except fish move and you can’t see them.”