Where wild country rubs shoulders with a freeway

Published 3:14 pm Friday, April 16, 2021

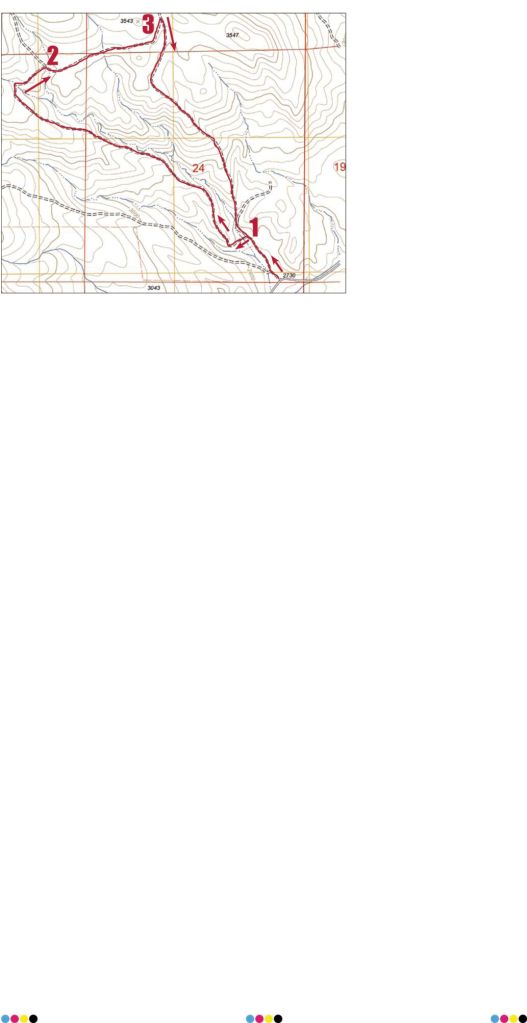

- The large numbers correspond to the three road junctions mentioned in the story, and the arrows indicate direction of travel for hiking the loop clockwise.

The view was quintessential wilderness except for the 18-wheelers rolling by on the freeway, almost near enough to discern the name of the trucking company on the trailer.

And absolutely near enough to hear the exhaust moan as the drivers downshifted to make the grade above Pritchard Creek.

Of course wilderness is just a word.

And it’s a word, whether deployed as a noun or an adjective, whose definition, much like beauty, is determined by whoever’s doing the looking.

When I’m hiking I prefer the typical symbols of wilderness — mountain peak, glacial lake, primeval forest — to the freeway’s cacophony, diesel aroma and flotsam of soda cans and hamburger wrappers whipped about by the incessant artificial wind.

But I also appreciate the rare occasions when these two worlds, so different, rub shoulders in what seems a comfortable companionship.

I came across such an intersection recently above the Durkee Valley, about 20 miles southeast of Baker City.

It all started with a map.

(Many of my experiences do; I would rather be a cartographer than almost anything else, but I lack any of the requisite skills. My complete absence of artistic ability alone disqualifies me absolutely from the profession.)

I was nosing around a web-based map, searching for a short and nearby hiking spot that I hadn’t visited. I noticed a series of roads branching off the Burnt River Canyon road, on the west side of the Durkee Valley.

I had driven past the intersection many times but always on my way to a different destination.

I vaguely recalled, though, that I had assumed on those occasions that the roads either didn’t go far, or that they ran into private property.

But when I checked my paper BLM map I was pleasantly surprised to see that the roads head straight into a considerable chunk of public ground — a bit more than four square miles all told.

And at least on the map — and with the more detailed view from Google Earth’s satellites — it appeared that a loop route was feasible.

Along with my wife, Lisa, and our kids, Olivia and Max, I drove to Durkee Valley on Easter Sunday, one of the few days this spring when the wind wasn’t beastly.

It was in fact a fine morning, with the temperature in the 60s, more typical of early June than of early April.

The dirt road heads northeast, on the right side of a dry gulch. After a few hundred yards we reached the first junction, and the start of the loop. I had checked the route on a topographic map and it looked as though the left fork had slightly less steep grades, so we went that way.

The road — now little more than a path, although accessible for four-wheel drive, at least when dry — crosses the gulch and then climbs the shoulder of a ridge.

The slope is taxing at times but my attention was diverted in the short range by wildflowers and in the long by the increasingly expansive views.

The sandy brown soil was carpeted in places by phlox, my favorite early spring bloom. It’s a low-growing species — what you’d call a ground cover in a garden — and its blossoms, usually pink or an intense purple, brighten the dull hillsides from a football field away.

The road gains about 600 feet in elevation as it ascends the narrow ridge. We paused for a minute to have a drink of water and enjoy the view, which included the heart of Durkee Valley and the snowy ridges south of the valley.

This is the classic transition zone between sagebrush steppe and the pine-fir forests of the uplands. There are plenty of trees, all of them western junipers, the lone conifer that can tolerate the arid climate here.

I was surprised at the diversity of the terrain. This of course is one of the great rewards of venturing off the main routes — to understand more intimately what lies between the folds of the land, hidden from all but the adventurous traveler.

For instance, the gully just to the north of the road was a contorted badland of rock pinnacles and colorful ashy swathes not so dissimilar from the Painted Hills near Mitchell, though not nearly so dramatic or photogenic.

Still, when I stood beside the car and looked up at our intended route I had no conception of what I was going to see.

The road veers sharply to the right at the head of that gully. We watched a herd of about a dozen mule deer gambol across the slope above, winding among the junipers in their uniquely graceful, somehow dainty, gait.

The road crosses the gully and soon after reaches the second junction in a grassy saddle.

Here the views open to the north, dominated, as is the case throughout the Durkee country, by the bald summit of Lookout Mountain. At 7,120 feet it is the tallest peak in the southeast corner of Baker County, and it commands the terrain in a way befitting its name.

(It’s also, appropriately enough, the site of a Bureau of Land Management fire lookout, which is used each summer.)

The road heads straight toward Lookout Mountain for a quarter mile or so to the third and final junction. The bonus here is a brief but stirring glimpse at a small section of the Wallowas. This greatest of our mountain ranges in Northeast Oregon seems almost Himalayan from this vantage point. It is a singular experience, it seems to me, to stand in what is in effect a desert landscape and to see, in the distance, an alpine world of snowfields and granite horns and high meadows that will still be green and lush with frigid snowmelt in August, when the grass we’re walking through will long have gone to seed.

This is another sort of juxtaposition, but not so different from the confluence of wildland and four-lane freeway.

From this last intersection it’s almost all downhill, with the interstate occasionally visible several hundred feet below.

Extremely downhill, in a few sections.

For what might have been the first time, all four of us agreed that I had made the right decision to hike the loop clockwise.

(I almost always endorse my route-finding choices, but mine typically is the lone voice, drowned out by the familial choir.)

This road, which also clings to the spine of a steep and narrow ridge, also reveals an intriguing basin, similar to the one mentioned earlier but larger and more varied in its collection of stony sculptures. It’s the sort of place that in a national park probably would be penetrated by a paved path.

The loop is about three miles, with an elevation gain of around 700 feet.

From Baker City, drive east on Interstate 84 and exit at Durkee, near Milepost 327. Turn right at the stop sign and drive through the “downtown” of the unincorporated town of Durkee, named for a pioneer family. After a third of a mile, just beyond the railroad tracks, turn right at a stop sign onto Old Highway 30.

Drive west on Highway 30 for 1.5 miles, then turn left onto paved Burnt River Canyon Road. Follow the road, which turns to gravel, for 2 miles. There is an open area on the right side of the road with plenty of room for parking. There’s a BLM sign noting that the primitive road is not suitable for passenger cars or trailers.