Main Street: Inside the Klavern — fear and loyalty

Published 6:15 am Wednesday, February 16, 2022

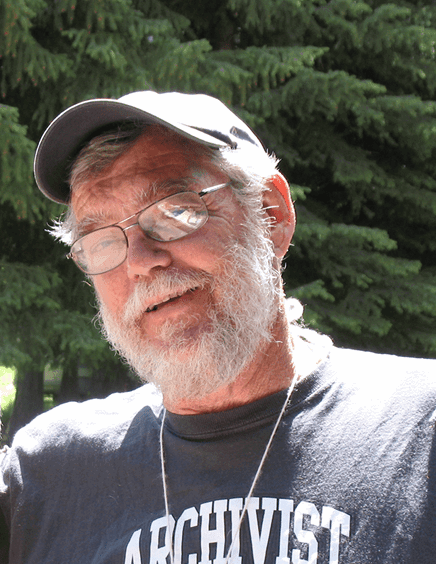

- Wandschneider

“Inside the Klavern” is a book published in 1999. The subtitle is “The Secret History of a Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s.” The place is La Grande, Oregon.

In January of 1968, Colon R. Eberhard, an 86-year-old “former state legislator, school board commissioner and Masonic lodge master of La Grande,” was fatally injured by a car while crossing the street. When the contents of his safe were processed for probate, an unlabeled folder containing 200 pages of minutes and commentary of the La Grande KKK was found along with, but separate from, 63 years of the respected attorney’s legal files. They covered the years 1922-24, beginning in May, making it almost exactly 100 years ago that the La Grande klavern started business.

The stash remained in the hands of a local lawyer, was looked at and copied by another lawyer — who was Catholic — before being turned over to the Oregon Historical Society. The copy made its way into the hands of a reporter at the La Grande Observer in the mid 1980s, and a surviving Klan member was interviewed for a story.

I have vague memories of hearing about the La Grande Klan, and remember clearly Lola Hopkins, a Protestant Johnson who married Catholic Joe Hopkins, telling me about a cross burning outside of Enterprise. And, more recently, there is the story, told by Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center director Gwen Trice, of a Klansmen visit to Maxville. The white superviser told the robed visitors that he knew exactly who they were under their white hoods, and that they had better get on home, which they did.

More recently, Rick Swart told me that in his last months as editor of the Chieftain, he had begun a file on local, Wallowa County, activities of the Klan. He didn’t know where the file was now, but the conversation with him and his mention of the book reignited my interest.

I ordered it, and have been making my way through a series of clipped messages about patriotism, Prohibition, public school education and camaraderie among the La Grande Klansmen and those from neighboring klaverns in Baker, Pendleton and Elgin. There is a lot about titles, robes, initiations, helping the sick and downtrodden and about the evils of drink and Catholicism.

Negroes, Jews, Asians, the Irish and new immigrants all come in for criticism, but it is the Catholics who were the spurs in La Grande Klansmen’s sides. Catholics managed one of the town’s banks, a few businesses, including Herman’s lunch counter, and had insinuated themselves into the public school — while educating their own children in parochial schools.

The original KKK had risen and fallen after the Civil War, was revived again in 1915 in Georgia, and spread rapidly across the country. Oregon was particularly fertile Klan land, with big chapters in Medford, Eugene and Portland, and a governor, Walter Pierce, who might have been a member but was surely sympathetic to the Klan. He was a La Grande-area farmer, and spoke at La Grande Klan meetings, where he was called a “Klansman.” The library at Eastern Oregon University is named after him.

The gist of things in La Grande was that 200-300 members met frequently and patted each other’s backs, shamed people who patronized the German Catholic butcher and joined with others across the state to help elect Pierce and pass an education bill which made “public” education, aimed squarely at Catholic schools, compulsory.

Members were noted by occupation. There were mechanics and farmers, insurance agents, barbers, railroad workers and ministers. The mainline Protestant churches were heavily involved, as were the Masons. What the men shared was fears, which they assuaged with loyalty. The minutes are mundane. They don’t exude hate, but show fears and applaud the loyalties of members.

In 1922, recent and present fears were many: World War I must have taken relatives of those La Grande Klansman; the communists had taken Russia and had a strong U.S. presence; the country had suffered through the flu pandemic of 1917-18; the Temperance movement led to the 18th Amendment and Prohibition; and a new, urban, fast “jazz age,” which flaunted prohibition and convention, was on the rise.

Loyalty was solidarity and comfort. It was helping widows, buying hay for a down-and-out farmer, wearing the same white gowns and repeating the same oaths — and distrusting the same things: alcohol, Asians and, especially, Catholics, only 7% of the 1920s Oregon population, but “others” whose customs of worship and places of origin were foreign, who’d been accused of fomenting the Cayuse Indians against the Whitmans, who had parochial schools where they promulgated their own ideologies.

It’s tempting to catalog today’s fears — of pandemic, immigrants, government and, most seriously, a shrinking white majority, against those of 100 years ago.