Main Street: Language is the lens through which we see the world

Published 6:00 am Saturday, April 23, 2022

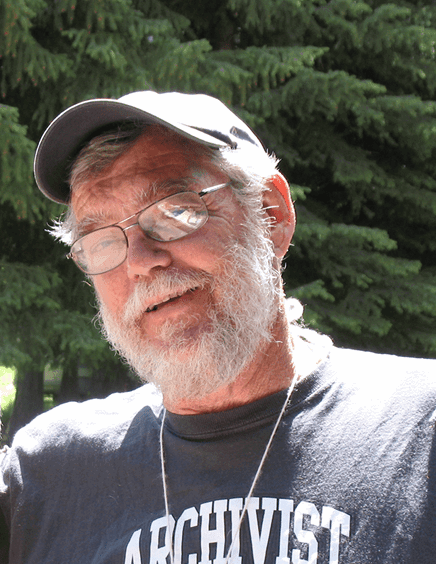

- Wandschneider

Bir lisan, bir adam …

In Turkish, that begins the saying, “one language, one person, two languages, two people,” meaning that we are literally different human beings when we fluently use another language.

I am thinking about this because I am going back to Turkey for only the second time in 52 years. I’m brushing up on the language, words and phrases coming to mind after long absences. “Fark etmez,” I automatically answer when someone asks whether I want coffee or tea — “Makes no difference.”

And when a friend comes down with COVID, I say “gecmis olsun” — “may it pass quickly” — like I would have 50 years ago. We don’t have anything that handy in English.

That’s the fun of it, but there is a serious side to language and its relation to knowledge and culture. Author Wade Davis says in his 2009 book, “The Wayfinders: Why Ancient Wisdom Matters in the Modern World,” that of the 7,000 languages then spoken in the world, half of them were not being carried down to the next generation.

Every two weeks, he said, an elder was dying and taking the last syllables of a language with her/him. He likened this loss to the loss of biological diversity. As we lose languages, we lose ways of seeing the world, ways of relating to other people. We lose part of the store of human knowledge.

I’m reminded that Alvin Josephy said over 50 years ago that the Americas had been inhabited by humans for more than 20,000 years, perhaps as many as 40,000. And he wrote that the population might have been as many as 90 million when Columbus hit the shore.

He based his thinking on languages. Linguists told him how long it took for a language to break off and become unique, and the explorers and missionaries and settlers with language curiosity documented approximately 2,500 languages spoken on the two continents in 1492. Linguists have measured and followed the dispersion of peoples across the continents with language from then until now.

In Alvin’s time, archeologists were spouting the Bering Land Bridge theory, postulating a crossing from Asia about 12,000 years ago. And many anthropologists said that the population, from the Arctic to the tip of South America, could not have been more than 10 million, that there were maybe a million inhabitants in what is now the United States.

They were wrong. Too many languages; too many peoples. There is now good documentation that as much as 90% of tribal populations were killed in early years of contact by European diseases to which they had no immunities. We have new findings on the Salmon River of 16,000-year-old settlements, and footprints in sand in the Southwest that date to 23,000 years ago. Coastal migration from Asia is now the theory. And modern DNA research shows migration patterns that follow the ways of language Josephy wrote about in “The Indian Heritage of America” — in 1968.

Language is the lens through which we see the world. My mother saw her world in Norwegian first, and then, embarrassed that his daughter didn’t know English, Grandpa Hagen said that they’d speak English at home. Mom hung onto the language enough so that she could talk secrets with her Minnesota friends in front of me growing up. I didn’t learn it.

I spent a summer working on a farm with Mexican laborers who’d come to California for the higher wages — 90 cents an hour. I had two years of high school Spanish and that summer of Tex-Mex Spanish. What a pity that I let it go.

The first colonists, from the British Isles, understood the confluence of language and culture. They saw Anglo-America as the arrow of civilization, led the new government with borrowings from England, engulfed immigrant populations with school and church English and sought to totally incorporate and assimilate American Indians by taking children from parents and putting them in boarding schools, outlawing their languages.

The wheel has turned, and American Indians are openly speaking old languages and reviving ones at the edge of extinction — about 250 individual languages, among them Nez Perce and Umatilla. I wish I knew enough to understand their complex family relationships — I only know that brothers, sisters, cousins, aunts and uncles have no direct translations and broader meanings than anything in American English.

And, thanks to an old Turkish roommate who has prodded me regularly on the phone for 50 years, and to a wonderful trip back in 2004, my four years of living in that language in that country is coming back. Not totally of course, but enough to say please and thank you, to know what to call elders and children, to say “Hos bulduk” — “I find my coming back good” — when I arrive.