Book battles are raging nationwide. A Washington library could be nation’s first to close

Published 1:00 pm Tuesday, August 15, 2023

- Voters in November could close the only library in Columbia County, the result of a yearlong dispute over the placement of young adult books that address gender, sexuality and race.

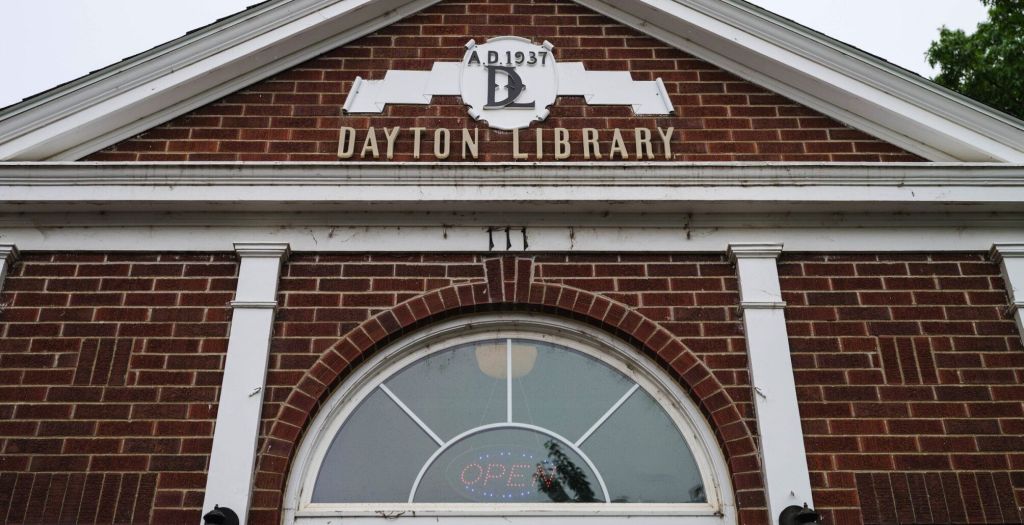

DAYTON — Book battles are raging across the nation, but none have carried the kind of stakes as the one here in Dayton, a one-stoplight farming community in the southeastern corner of Washington.

For the county’s only library, the battle has turned, quite literally, existential: Voters will decide in November whether to shut it down.

The library, which has occupied the same modest brick building a block off Main Street for 86 years, is at risk not because of a lack of funding or a lack of demand for its services. Instead, it could shutter because of a yearlong dispute over the placement of, at first, one book, then a dozen and now well over 100, all dealing with gender, sexuality or race.

It would be the first library in the country to close because of a dispute over what books are on the shelves, according to the American Library Association.

“That is the end of the library as we know it,” said Jay Ball, who owns a local auto shop and chairs the library’s board of directors. “It’s insane, it’s just insane.”

Dayton, Washington, is 114 miles north of La Grande.

Library opponents late last month submitted enough signatures to get on the November ballot with their argument that the library makes books dealing with transgender issues, sexuality, consent, race and gender stereotypes too accessible to kids.

Jessica Ruffcorn, the leader of the push to dissolve the Columbia County Rural Library District, says the library is “targeting kids with sexualized content.”

The library director and board initially refused to move any of the books. But, more recently, the library has tried to assuage its adversaries, eliminating the entire young adult nonfiction section and intermingling those books with adult books. They moved all sex-ed books into a new “parenting” section of the library.

It has not worked.

“We do not trust their motives to move the books,” Ruffcorn wrote in an email to The Seattle Times. “Now it’s up to unincorporated Columbia County to decide what our community standards are, and whether our library is an asset or a drain on our community.”

The voters guide statement against the library, written by three other library opponents, is even blunter: “This public library is an irretrievably compromised entity, and it needs to be removed from our midst.”

‘By far the most extreme instance’

The American Library Association documented nearly 1,300 attempts to censor books in libraries across the country in 2022, nearly double the number from 2021.

“There’s always going to be a book I don’t agree with on the shelf of the library,” Deborah Caldwell-Stone, the director of the association’s Office of Intellectual Freedom, said in a phone interview. “In arguing for the presence of a library and the presence of books on the shelf, what we’re supporting is the rights of each individual to make their own choices, for each family to make their own choices about what to read.”

“This particular instance, in Columbia County, where they’ve actually petitioned to dissolve the library district and it’s making it to the ballot, is the first I’ve heard of in our state,” said Brianna Hoffman, executive director of the Washington Library Association. “This is by far the most extreme instance.”

Other fights in Washington over books include nearby Walla Walla, where the School Board last year refused the demands of several parents who had wanted four books, including Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye,” removed from the high school library because of their handling of sexuality, race and profanity.

In Liberty Lake, a Spokane suburb, a fight over one book, “Gender Queer,” led the City Council to take over control of library policy before the mayor vetoed the plan.

Last year, the Kent School District stepped in to reverse a book ban after a middle school principal removed from the school library “Jack of Hearts (and Other Parts),” a young adult novel about a gay 17-year-old sex columnist.

Nationally, high schools in the Tampa, Fla., area last week said they would limit teaching Shakespeare over concerns that the sexual content could run afoul of new state rules. Florida last year led a wave of Republican-led states in passing laws that make it easier for parents to challenge books in school libraries.

In Jamestown, Mich., voters defunded the local library over a few books with LGBTQ+ content. It remains open only because of a burst of private fundraising, which could run out next year.

And Arkansas recently passed a law that would make librarians criminally liable for providing books or materials to minors that are “harmful” or “obscene.”

Here in Dayton, the dispute already has led to the resignation of the library’s director. If voters in unincorporated areas in Columbia County dissolve the Columbia County Rural Library District, state law dictates that the library’s books and materials will be sent to the Washington State Library in Tumwater, near Olympia. City officials would then decide what to do with the rest of the library’s property, including its building.

There is no known precedent for a similar library district to simply be dissolved, shuttering the library, said Derrick Nunnally, a spokesperson for the Secretary of State’s Office, which oversees the state library.

Nunnally said state officials haven’t determined how books would be moved to the state library or what they would do with them in the event the Dayton library ceases to exist.

Columbia County has about 2,800 registered voters. Roughly two-thirds of them live in the city of Dayton, where the library is located. But because the library is organized as a rural library district, state law says that only the 1,000 or so voters who don’t live in an incorporated city can vote on the library’s fate, even though Dayton residents pay taxes to fund the library.

The nearest library is in Waitsburg, 10 miles away in Walla Walla County. It’s open only 20 hours a week, and only Waitsburg residents can get a library card.

The dispute that set up the vote

The trouble started about a year ago in the library’s basement, which holds the kids and young adult books.

On display in the young adult section, next to “Geometry for Dummies” and underneath a series of Japanese “Demon Slayer” graphic novels, was a book called “What’s the T?” — described as “the no-nonsense guide to all things trans and/or nonbinary for teens.”

Ruffcorn and a small group of parents objected. The book contains sexual content and “was not age appropriate,” she said in an email. (She declined an interview request.) The book is a firsthand account of coming out as transgender and offers explanations and advice on identity, sex and relationships.

The group’s concerns quickly spread to other books they found in the kids and young adult sections. They wanted the library to move about a dozen of them, including “Our Skin: A First Conversation About Race,” “This Book is Anti-Racist,” “Yes! No!: A First Conversation About Consent,” and “When They Call You a Terrorist: A Black Lives Matter Memoir.”

The library director, Todd Vandenbark, declined.

“No one has the right to make rules restricting what other people read or use, or to make decisions for other families,” he wrote at the time.

Hoffman, of the Washington Libraries Association, said the books on the list are all found in “hundreds, if not thousands of libraries across the country.”

One book on the list, “Melissa,” is in more than 2,000 libraries, according to WorldCat, the world’s largest library catalog. That’s almost certainly an undercount, Hoffman said, as many smaller libraries maintain their own catalogs and don’t show up on WorldCat.

One person appealed Vandenbark’s decision on “What’s the T?” to the library board, which voted 4-1 to leave the book in place.

Ruffcorn, a mother of two who owns a small traveling boutique, and her supporters became regulars at the monthly library board meetings. Suddenly, the typically sleepy meetings were drawing upwards of 100 people.

Things escalated. Ruffcorn accused Vandenbark of being “a groomer,” writing on Facebook that he “invites vulnerable children to the library as a safe space.”

This spring, she began circulating petitions to dissolve the library. On Facebook, she changed her cover photo to the words “Let men be masculine again. Let women be feminine again. Let kids be innocent again.”

In June, Vandenbark, who had been a librarian at a small college in Iowa before moving to Dayton, announced his resignation, saying he was tired of the battles and was leaving Dayton. Vandenbark did not respond to a request for comment.

His replacement, Ellen Brigham, created the new parenting section. She moved young adult nonfiction books to the adult section on the main floor.

“We’re walking a really fine line between listening to people who have arguments and remembering that the majority of people who haven’t said anything still use the library,” Brigham said. “We have the entire community to serve.”

About 50 to 60 people typically use the library each day, more if there’s a special event.

For Ruffcorn, moving the books wasn’t enough. The list of about a dozen grew to 165 books “with a highly sexualized topic available downstairs.” Even after the young adult nonfiction was moved upstairs, more than 100 of those books remained downstairs, she said in an email that included, screenshots of several books she objected to, including, “It’s Perfectly Normal: Changing Bodies, Growing Up, Sex, and Sexual Health.” The book includes cartoonlike drawings of naked bodies, of couples having sex and of literal birds and bees.

“You cannot access porn on the library computers, but if you want to check it out in paper form it is ok,” Ruffcorn wrote.

Ruffcorn says there is an agenda to desensitize kids to sex. She says kids are not safe in the library to choose books on their own.

“It is the parent’s responsibility to monitor what their kids read,” she wrote. “However the library also needs to take some responsibilities in this as well.”

She worries about field trips and after-school programs at the library.

“Do we realistically think that those chaperones are going to be able to monitor every book the kids pick out, and is it still the parents’ fault for sending their kids to these programs?” she wrote.

At a board meeting last month, she asked for a full list of the books being moved and for changes to the library’s policies on collection development and book challenges. She also asked for the resignation of the chair of the library board and for the library to withdraw from the American and Washington Library associations.

And she submitted a petition to the county auditor — 163 signatures, well above the 107 needed to get on the November ballot.

Up, down Main Street in Dayton

Composed of just a few dozen blocks along the Touchet River, Dayton boasts both the oldest train depot and the oldest operating courthouse in Washington.

On Main Street, the Northwest Grain Growers cooperative displays current wheat prices on an LED sign ($6.90 a bushel for soft white, $7.87 for hard red winter).

“It’s a conservative community,” said Jan Budden, who owns a small shop on Main Street selling Old West antiques and Americana. “I think they probably could find a way to shelve the books differently. Advertising an agenda is not a job for the library.”

Columbia County voted 70% for Donald Trump in 2020, the third-highest share in Washington.

A few doors down, Mindy Betzler is the owner and sole full-time employee of Dingle’s of Dayton hardware store, on Main Street since 1920. With a dozen or so cookbooks — “Weber’s Charcoal Grilling,” “Mac & Cheese Genius” — Dingle’s would be pretty much the only in-town source of books if the library closes down.

“If you don’t want your kid to read it, don’t let ‘em,” Betzler said of the controversy. “It’s kind of heartbreaking that such a few people can cause such a stir.”

Elise Severe brings her three daughters — Lauren, 7; Madelyn, “almost 5,” and Stella, 3 — to the library once a week or so. It’s been a key activity this summer, between golf camp, swim camp and vacation Bible school.

“I never in a million years thought I would have to fight to keep my library,” Severe said. She intends to help with a “positive information campaign” ahead of November, reminding people of the services the library provides.

Severe, who runs a local political action committee supporting moderate candidates, arrived at the library with her kids on Monday afternoon. But they realized they couldn’t check out any books. Someone had forgotten “The Berenstain Bears Forget Their Manners” at home, and it was overdue. Alas, they made do.

They headed straight to the basement. Bookshelves rim the perimeter of the room. Durable board books for toddlers are on the south side of the room and segue to picture books, chapter books and a young adult fiction section on the north end.

In the middle are toy trucks and farm equipment, train tracks, stuffed animals. There’s a semicircle of multicolored foam chairs. A small aquarium could use a cleaning.

Lauren played with a train set. Madelyn poked at the aquarium and its few beleaguered fish.

A couple of older kids played games and watched TikTok on computers nearby.

The library’s opponents “present themselves like they are the moral compass for everyone,” Severe said.

“You do what is best for you and your family. I will never insert myself into the way you want to teach or educate your kids.”

Upstairs, Zella Powers, 85, worked on one of the library’s public computers, just reading the news, tootling around, one of a few dozen people a day who come to use the library’s internet.

“I don’t have a computer at home. It’s easier to have it here, and they can help me do it,” she said, gesturing toward Brigham behind the front desk. “This could have all been avoided if both sides sat down and sincerely talked.”

‘It honestly terrifies me’

Deb Fortner’s family has farmed wheat on land about 15 miles outside Dayton for four generations. During harvest season, Fortner and eight employees work 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. to cut the wheat and get it to a grain elevator.

“I kind of live under a rock,” Fortner said. But she started hearing rumblings about the library brouhaha, read articles in the weekly Dayton Chronicle and saw social media postings about “What’s the T?”

So she decided to check it out firsthand. She downloaded the book’s audio version and listened to it as she drove her 25-ton John Deere combine through her fields, reaping, threshing and winnowing hundreds of bushels.

“So I listened to that book in two days,” Fortner said. “It was a lovely book. There is nothing offensive in that book.”

Fortner is now helping lead the campaign to save the library along with Tanya Patton, who is essentially the godmother of the modern Dayton library. Patton served on the board for 14 years, 13 as chair. She tried to keep her distance from the current fight. But she’s been pulled in to try to save it.

Patton carries a file of photocopied old newspaper articles — from 1935, 1974, 1999 — telling the history of the library: how a group of Dayton women fundraised for 19 years, how it finally got built with the help of the New Deal Works Progress Administration and $5,000 from then-Gov. Clarence Martin, how a wealthy local couple paid for a small addition that became the city’s only public meeting room, open to all.

Patton led the campaign in 2005 to create the rural library district. The city of Dayton had always funded the library, dating back to its creation in 1937, but resources had dwindled.

The city was providing enough money for only two part-time librarians to open the library 20 hours a week. The city had no budget for new books.

Patton had four school-age children at the time. The library and 4-H were the twin pillars in the kids’ lives.

Staring at another funding cut from the city, “you get to this critical mass of, is this library even going to survive?” Patton remembered. “You become a nonessential service really fast compared to streets and roads and sewers. It was too important to turn my back on.”

So a push was made for the county to take over funding.

The campaign was successful, with 59% of county voters agreeing to a new taxing district to fund the library. (The vote was 382 to 268.) A few years later, voters annexed the city of Dayton into the library district, so that both city and non-city residents paid the same property tax levy to fund the library, even though Dayton city residents can’t vote to keep it open.

A decade and a half later, it’s all at risk. Patton and Fortner plan a messaging campaign — a fact sheet, social media, flyers — to inform voters of the library’s value.

“The jump from, ‘OK, you won’t move these books,’ to ‘So we’re going to close the only library in the county’ is something I still don’t understand,” Patton said.

“Our democratic republic was built on this access to information,” she added. “This isn’t just about Dayton. This is about something bigger. And it honestly terrifies me.”