Situation critical

Published 7:00 am Monday, March 31, 2025

- From left, veterinarian Kelli Kidd, with assistants Lydia Wheeler and Blanca Valverde, checks on Montgomery after the cat had a procedure Feb. 26, 2025, at Animal Urgent Care in Milton-Freewater. (Sheila Hagar/For the East Oregonian)

Rural communities lack veterinarians; suicide rates, clinical depression high in the profession

Spice was not very happy to be at the Animal Urgent Care on Highway 11 in Milton-Freewater on a recent Friday morning.

Cory Egan and Erika Long’s cat, adopted from the Pendleton Animal Welfare Society, gets care in Milton-Freewater from veterinarian Kelli Kidd.

Kidd owns the walk-in urgent care clinic with partner and veterinarian Patrick Kennedy. They also own a standard practice, Kennedy Veterinary Services, and a pet euthanasia business, Soft Landing Veterinary Center, in Milton-Freewater.

Trending

Although Egan and Long live 45 minutes away in Pendleton, Kidd’s highway location works best for them, the married couple said.

Initially Spice was brought to Kidd after adoption for concerns about worsening congestion. Now, this clinic is the one consistently open on the single day off Egan and Long share, they said.

“We live in a rural area, so you have to expect that,” Egan said of the travel time.

Indeed, animal medical care, or rather, the scarcity of it, has risen to a hot-button topic in the industry.

Demand is ‘pretty difficult to meet’

Although some experts say the nationwide shortage of veterinarians is due to end in the next 10 years, no one is denying there are problems getting enough veterinarians right now, experts say.

The American Association of Veterinary Medical Colleges’ 26-page report from 2024 states “an inadequate supply of veterinarians endangers the long-term wellbeing of patients, while an excess supply increases veterinarian unemployment and wastes the resources expended on program expansion.”

Trending

The report’s authors noted there are contradicting studies on those dueling projections, but two demographic shifts may decrease the average working hours of veterinarians, thereby decreasing the effective supply.

“The profession is undergoing a shift toward an increasing number of female veterinarians, and retiring Baby Boomers are gradually being replaced by members of the Millennial generation and Generation Z,” the report notes.

In both cases that can mean veterinarians working fewer years in the field and-or less weekly hours.

It all trickles downward to clients who need medical care for their pets, livestock and horses.That’s especially true in rural areas, and Eastern Oregon is no exception.

Charles Hurty, a veterinarian in Newport, said rural areas in the state are underserved and there is growing concern.

“There is a demand that’s pretty difficult to meet,” he said, noting the small city of Florence recently lost its sole veterinary practice and no one stepped forward to buy the business.

Hurty has worked three decades in animal medicine and is the immediate past president of the Oregon Veterinary Medical Association.

The organization, the only one like it in Oregon, advocates legislatively for its more than 1,000 members in many aspects of veterinary care and business.

There are many issues surrounding the shortage of vet care, Hurty said.

“I think a big part of it is the education debt veterinarian students have; $185,000 is the average and up to $300,000 for some. Typically, in rural areas, the pay might not be great enough to cover it,” he said.

That can drive new graduates to metro areas — sign-on bonuses there are often hefty, the hours more predictable and “there are more options for life. It’s hard to compete with as they look at starting a family and buying a house,” Hurty said.

In rural practices the work-life balance is different, with plenty of large-animal emergencies that come in the middle of the night. “About half who start in rural practice end up leaving for positions that don’t demand long on-call hours.

Rural rewards

Joe Klopfenstein has heard all of this, many times over. As associate dean of Oregon State University’s Carlson College of Veterinary Medicine, he’s participated in panel discussions and spoken to reporters about the veterinarian outlook.

OSU’s veterinarian school opened in 1983, and remains one of the smallest in the country; about 80 students will graduate this year.

The animal care industry suffers from a lack of marketing, failing to convince more people veterinary medicine is a great profession to go into, Klopfenstein said.

Moreover, the rural piece often gets short-shrifted, according to Klopfenstein.

Large animal — sometimes called food animal — care is challenging. It pays well, however, as ranchers and others invest in keeping their animals alive.

“In the mixed-animal practices, some people are not as ready to spend that kind of money on a pet,” he said

The rural-practice time commitment is high and compensation is lower — but so is the cost of rural living. “Much lower,” Klopfenstein said.

What many graduates haven’t yet learned is the personal reward that comes in a small-town and ag-based practice, Klopfenstein noted.

“No one enjoys when the phone rings at 10:30 at night and a cow is out in the pasture, trying to have a calf. It’s no fun, but it’s a necessary part of having a practice. But the reward is so great … People really do appreciate you being there for them,” he said.

Independent practitioners vs. corporate entities

He’s never considered turning down a patient who needs emergency care, said Terrence McCoy, the owner of Animal Health Center in La Grande since 1989.

“I think ‘You take your client, you take their emergencies,’” the veterinarian said.

That’s not a popular stand today, for two major reasons.

One is that the vet field is becoming part-time work, he feels, and the other is that large corporate veterinary care businesses are running the show in many places.

Less common in less densely-populated areas, the corporate model buys up independent practices, taking the veterinarian-owner out of the decision-making role.

In general, drawbacks of a corporate-owned clinic can include an emphasis on quick turnover of cases, little-to-no payment flexibility for customers and pressure to meet financial benchmarks, according to area veterinarians.

As well, the culture of the independent clinic changes by a high-pressure environment, and that leads to burnout, noted “pets.care,” an online consumer advocacy group for the pet care industry.

McCoy prides his business on having the opposite attitude, believing it pays off inside and outside the clinic.

“We’ve worked hard to have our veterinarians involved in the community. We are very active with FFA and 4-H, we did 420 low-cost spay and neuter operations for four organizations,” he said.

Corporate-owned veterinary places are not buying a child’s Future Farmers of America pig at a show, they are not contributing money to youth activities, McCoy pointed out, noting neither are the online and box store pharmacies selling animal medicines.

“They don’t pay property taxes, they don’t support the schools. I am paying those taxes and I support my community, he said.

Veterinary corporations also are not encouraging local young people to consider veterinary medicine for their career. “We work hard to get them to school and get them back here,” the La Grande veterinarian said.

“We are back to four doctors in May. She’s a local gal and we’re tickled.”

His staff stays on top of the training required to serve their client base of small animals, horses and food animals. McCoy is committed to purchase equipment to facilitate an extensive scope of services, such as ultrasound, digital X-ray and orthopedic treatment.

Not everything pays for itself. “But if you don’t have it, that affects your ability to do services,” McCoy said.

Animal Health Center fields calls from all over the region, thanks to a lack of veterinarians and vet technicians in Eastern Oregon.

“I used to know my volume numbers. Now we’re just lucky to get through the day,” McCoy said.

More pets, more need

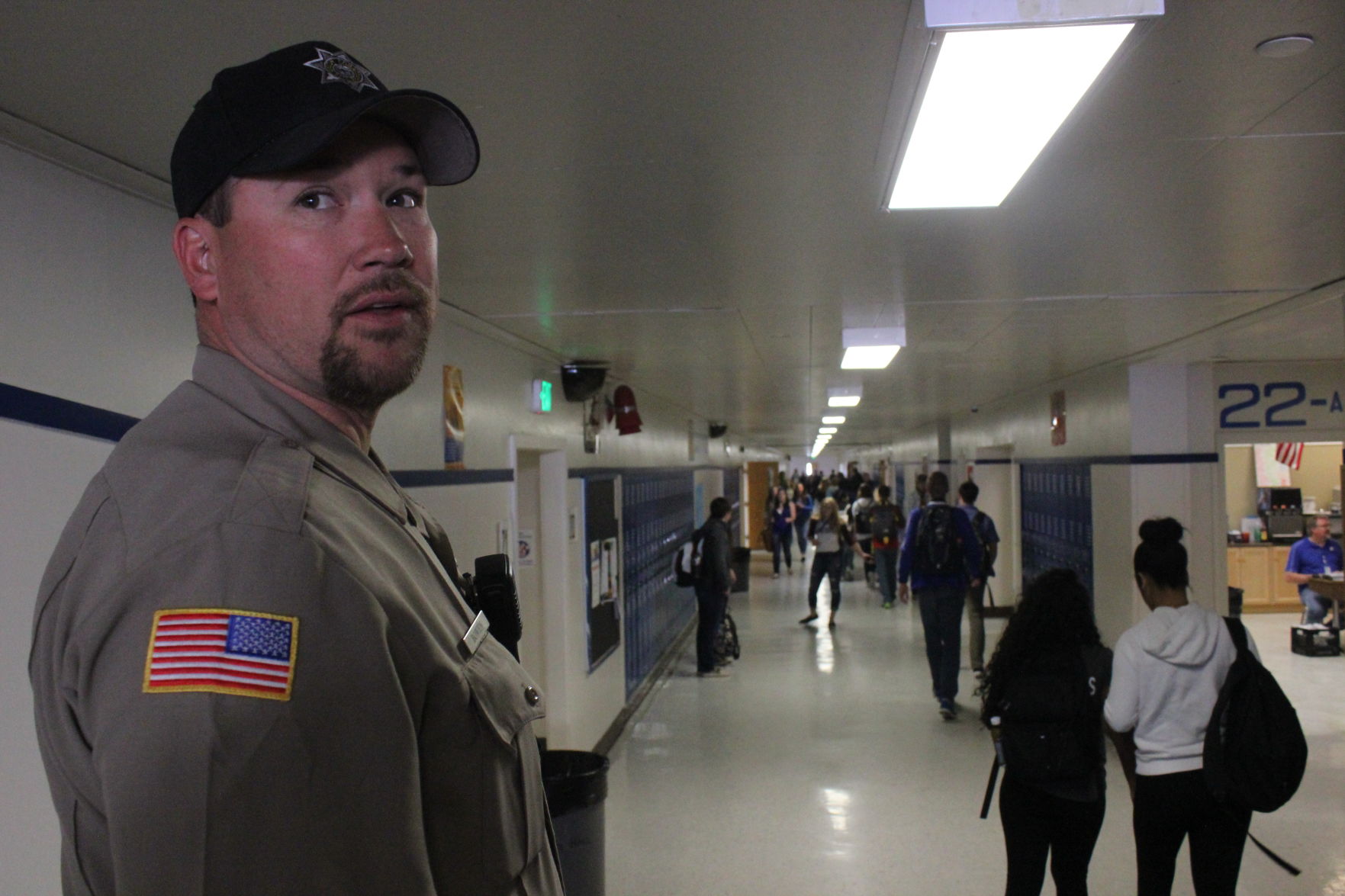

At Urgent Animal Care in Milton-Freewater, more clients were showing up on that day.

Joel Morgan had brought in Cupcake, a Shih tzu-poodle mix. The dog had bloody diarrhea that had reached the urgent stage, Morgan said, and he hadn’t been able to get into his regular vet.

“I’ve been wracking my brain to figure out what happened. We’re not sure if she got into something,” he told the veterinary assistant behind the counter.

Nearby sat Shauntel McKnight of Pendleton, with her elderly dog. Remi was at the clinic for a tumor, McKnight said.

Veterinarian Kelli Kidd had plenty of help that morning, but she doesn’t take that for granted.

Kidd affirms the veterinarian shortage is felt harder in rural spots on the map. She, too, sees the problem in layers.

Many more veterinarian graduates are women. That’s wonderful, she said, but young women, mostly, start families and don’t necessarily want to work full time afterward, Kidd said.

“So it takes more vets to fill the same number of hours,” she said.

The pandemic seems to have been a real turning point in vet care, Kidd said.

Animal adoption rates shot way up for many reasons, including the company pets provide and that people were working from home. Without being able to go out and spend money, more people had the time and funds needed for pet care.

At the same time it was harder to practice animal medicine, given the constraints put in place to control spread of the coronavirus, she said.

The situation put a big demand on practices, while costs rose at the same time. It’s all grown worse as corporations buy up clinics and set higher prices, Kidd and others said.

Kidd estimates all but three veterinary practices from Walla Walla to Pendleton are now owned by corporate entities.

None of this has helped draw vet graduates to rural communities, who are under great pressure to make good money right away, she added.

Health costs to providers

Whenever the pendulum swings back to more veterinarians in the field — which the American Veterinary Medical Association estimates will happen in the next 10 years — it might not be enough to fill the deficit in smaller communities, Kidd predicted.

Much of this workforce is retiring, and suicide rates among veterinarians is alarming, according to a report the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association published.

The 2019 study found veterinarians in the United States are three-to-five times more likely to die by suicide than the general population.

A U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study that year reported nearly 400 veterinarians died by suicide between 1979 and 2015.

It’s estimated about 80% of all veterinarians suffer from clinical depression at some point, and about 50% report feeling unhappy in their careers, a TIME magazine story noted.

Clients’ emotions can contribute greatly to the stress level, Kidd said. Not only is their pet going through some kind of medical trauma, there can be issues paying for that care.

“There is sticker shock. And people take it out on the vets, when we’re just asking to be paid for our services,” she said, emphasizing that most people are lovely and grateful.

In a corporate practice, such a lack of funds could mean a client gets turned away.

“If you bring in a kitty with a broken leg, we’ll find a way to make it work … That lets me sleep at night. But in a corporation, I might get fired for that.”

Meantime, Kidd and Kenndy continue a perpetual quest to fill out their staff, including with at least one more veterinarian.

“I would get two full time vets,” Kidd said, “if I could.”