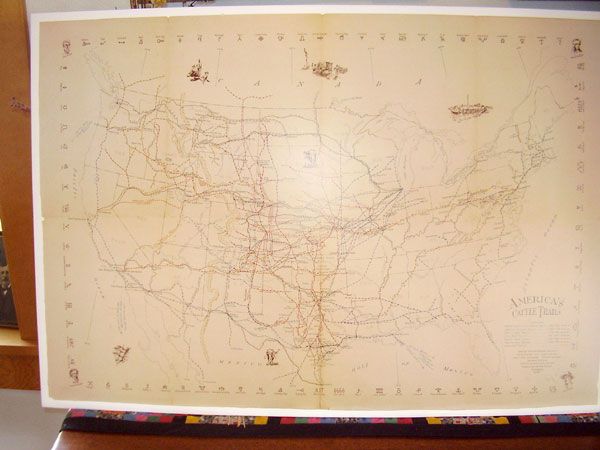

Historic map illustrates ‘America’s Cattle Trails’

Published 3:57 pm Friday, January 2, 2009

- CATTLE COUNTRY: The Union County Museum and Union County Cattlemenâs Association are selling copies of the map. Submitted photo

IMBLER – The history of cattle trails created by cattle

barons like Francisco Coronado, Charles Goodnight, Colonel Wheeler,

Jesse Chisholm and others has been illustrated on “America’s Cattle

Trails” map available to the public through the Union County

Cattlemen’s Association and the Union County Museum Society.

Local cattle rancher Sharon Beck, who has been involved with the

Cattlemen’s Association for 40-some years, said that the original

trails map was thought to have been drawn on rawhide, bearing darkened

fold lines throughout. It detailed some of the historic trails created

from 1540 through 1895.

The project of creating one map with all the known cattle trails was

undertaken by researchers Garnet M. Brayer and Herbert O Brayer,

accompanied by cartographer Hugh T. Glen and illustrator C.O. Froid.

The work was sponsored by Walco International Inc., one of the largest

U.S. distributors of animal health care products, and the Cowboys Then

and Now Museum of Portland.

“The Cowboys Then and Now Museum in Portland was supported by the beef council,” said Beck, “but it was very expensive to run, so it was sold to the Union County Museum Society.”

Among the attic treasures that the Union County Museum Society received were prints of the historic cattle trails map.

“The only other place I’ve found one map like it was in the rare book section,” said Beck. “The map was drawn in 1942, and the book was published in 1992 with the map included. It was published in New York.”

The printed maps illustrate six cattle trails in addition to one overland trail. The earliest among them is the Spanish and Mexican colonial trails dating from 1540 to 1846. In the 1540s, Francisco Coronado drove a herd of 1,500 longhorn into the Southwest. These were the forerunners of the longhorns we see today.

“Prior to the Civil War, most herders were Mexican vaqueros, and it is from their culture that many common terms and customs derive, such as the lariat, branding irons and boots,” wrote trails researcher Gene Lamm, author of “Dawson, Goodnight and the Great American Cattle Drives.” “Unbranded cattle were later named after a Texas lawyer named Sam Maverick, who had let his herd roam unmarked.”

The illustrated map also notes exports of cattle. Herds driven to Portland were eventually loaded onto boats on the Columbia River and shipped to the Hawaiian Islands. Trails from Texas led through Baker City and Northeast Oregon.

“Cattle wintered at Hot Lake,” said Beck, “and then were taken to the gold fields of Idaho and California.”

Cattle driven on trails to New Orleans were put on boats bound for the East Coast of the U.S. but also to the West Indies, Cuba, Haiti and other lands.

Surprisingly, the first interest in cattle was not for meat.

“Cattle were used primarily for their hides, tallow and horns and had relatively little (other) value as most

Americans at the time ate pork and Indians much preferred buffalo to beef,” wrote Lamm.

Consequently, the cattle trails map shows San Diego as a popular port for the export of hides to Peru and New England between the years 1812 and 1850.

In the 1850s as populations grew in Boston and throughout New England, cattle became desired for meat.

“Herds were driven up from Texas to the first railheads in Missouri, but longhorn cattle carried a tick to which they, but not other cattle, were immune,” wrote Lamm. “Outbreaks of Texas fever led local farmers in Kansas and Missouri first to set up blockades and then to pass legislation prohibiting Texas herds from entering their states.”

Once the Civil War began, however, cattle drives to the north were understandably interrupted. Cattle were re-routed eastward across the Mississippi River and made available to feed Confederate soldiers.

After the Civil War ended in 1865, Chicago became a major trail destination due to its meatpacking plants and rail connections to Sedalia, Mo., an important railhead for the Texas cattle drive of 1866.

“The cattle were driven hard,” said Beck, “but that’s how people got fresh meat – on the hoof.”

Cattle drives were long, dusty and often took weeks. The trail boss rode ahead, scouting for water and pasture. The chuck wagon followed in front and off to one side. About 20 drovers kept the 2,000 to 3,000 head of cattle calm and under control.

They exchanged positions and horses often and spoke to each other only in low voices. At night they sang their lonesome songs to lull the herd into a passive sleep. The greatest threat to a herd on the trail wasn’t the Indians but a stampede.

“Besides the danger to men and cattle,” wrote Lamm, “a four-mile run could burn off 50 pounds from a steer and at the end of a drive, meat meant money,”

America’s rich history of cattle trails is depicted on this map, including 82 different brand marks, seven trails, railroads, state boundaries and trail destinations with city names in the U.S. and Mexico.

To inquire about the “America’s Cattle Trails” map, contact Beck at 963-3592 or the Union County Museum Society. A sample of the map can also be viewed and ordered through The Mitre’s Touch Gallery

(963-3477) in Pat’s Alley,

La Grande. Proceeds go to advance the projects of the Union County Museum and the Union County Cattlemen’s Association.