Ranchers, ODFW gather in Wallowa County to talk wolves

Published 3:00 pm Sunday, May 26, 2024

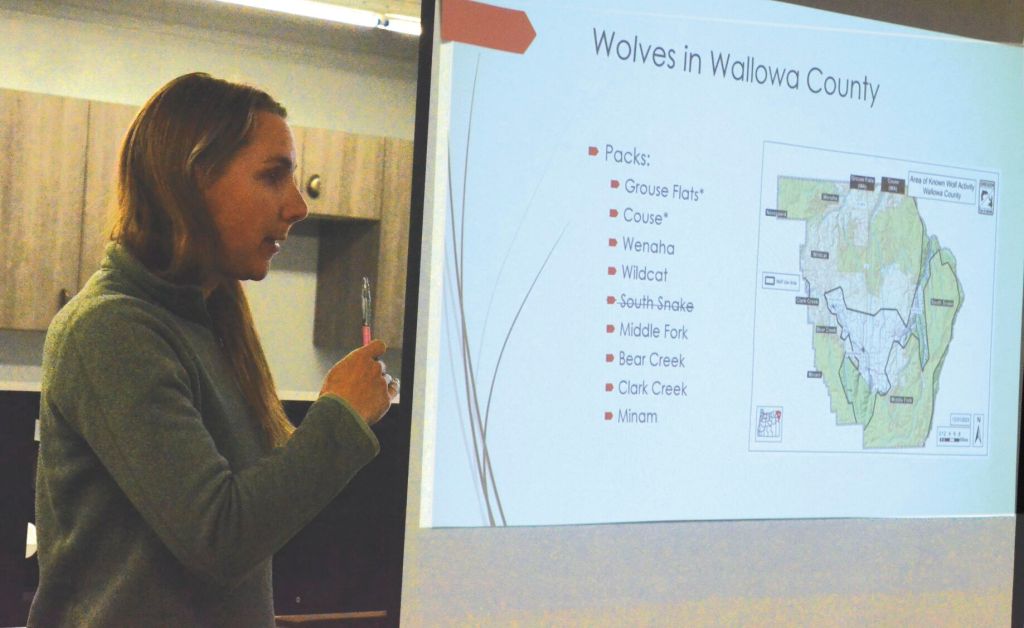

- Holly Tuers-Lance, an assistant wolf biologist with Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, shows a list of the wolf packs in Wallowa County and a map of their approximate locations May 21, 2024, during a meeting between ODFW and Wallowa County Stockgrowers in Enterprise.

ENTERPRISE — A small gathering of ranchers, police and representatives of the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife resulted in increased understanding of Northeast Oregon’s problem of wolf-livestock conflicts Tuesday, May 21.

About a half-dozen ranchers and the same number of ODFW officials, along with Wallowa County Sheriff Ryan Moody and Sheriff’s Sgt. Paul Pagano, gathered at the food booth of the Wallowa County Fairgrounds to learn more about what the state is doing to manage wolves particularly in Wallowa County, where the bulk of wolf attacks on livestock appear to occur.

John Williams, co-chairman of the Oregon Cattlemen’s Association’s wolf committee, as well as a rancher and longtime Oregon State University Extension agent, served as moderator.

“You can disagree as much as you want, but don’t be disagreeable,” he said.

Participants in the meeting were largely agreeable to Williams’ caution.

Improvement

Williams recalled that in January, ranchers in the Flora area met with ODFW agents to hear what the agency is doing to manage wolves in the county. Over the past couple of years, he said he’s seen improvement.

“I have seen wolf management in Oregon change,” he said. “I’ve seen it change most in Northeast Oregon because we’re where it’s mostly needed. The second thing I’ve seen is that in December, (the ODFW Commission) chose not to reopen the wolf plan. … They said what we have to do is figure out wolf management in Northeast Oregon because if you can figure out wolf-livestock conflicts in Northeast Oregon, you’ve got the rest of the state figured out. We’ve also got to figure out the poaching thing and we’ve got to figure a new way of counting wolves.”

According to the wolf report released earlier this year, at the end of 2023, 178 wolves were known in Oregon — the same number as at the end of 2022. They are counted individually in Western Oregon and by the pack in Central/Eastern Oregon. A pack is defined as four or more wolves traveling together in winter. Twenty-two packs were documented at the end of 2023, with a mean pack size of six wolves. In addition, 13 groups of two or three wolves were identified. At the end of 2023, 15 packs were documented as successful breeding pairs, two less than 2022.

State Rep. Bobby Levy, who was not at the meeting but visited Enterprise on May 22, said the city of Enterprise is the only part of Wallowa County that does not qualify as an area of known wolf activity. She and others disagree with the number of wolves the wolf report counted — stakeholders mostly agree that the number is an undercount — but ODFW is working to improve its method of counting them.

The packs

Holly Tuers-Lance, an assistant wolf biologist for the ODFW, listed the wolf packs currently in Wallowa County and showed a map of their approximate range. She listed the Grouse Flats, Couse, Wenaha, Wildcat, Middle Fork, Bear Creek, Clark Creek and Minam packs. One pack, the South Snake Pack, appears to have dissolved since three wolves — including the breeding pair and a juvenile — were found dead from February through March by Oregon State Police in the Lightning Creek drainage area, a tributary to the Imnaha River, apparent victims of a poisoned cow carcass. Among the remains were those of the wolves, eagles, a cougar and a coyote.

She said the alpha male of the Wenaha Pack also was poached and is not sure if its mate will survive.

“That puts us on the front page of the newspaper and that’s not where we want to be,” Williams said.

He noted that poisoning wolves is not only illegal, but harms other wildlife and pets and gives the livestock industry a bad name.

While it’s necessary to take out depredating wolves, he said, “poaching is unsustainable and inappropriate,

Handling a kill

Brent Wolf, the district wildlife biologist for the Wallowa Wildlife District, explained the proper procedure for a livestock owner to follow when he discovers a wolf-killed animal. First, he said, photograph the carcass and then cover it well with a tarp so no other animals feed on it. This is particularly crucial if it is suspected poison has been involved.

Then make a phone call — ODFW, the Sheriff’s Office or Oregon State Police.

Williams said one area he’s seen progress in working with ODFW is their relaxation of investigation criteria.

“It used to be if ODFW didn’t see it, it didn’t happen,” he said.

But not so any more. They’ve even eased up on the criteria for determining if a kill was by a wolf or not.

If it’s judged confirmed, that would be because there is physical evidence linking the kill to a wolf, such as bite marks, tracks of a wolf and other such evidence.

A “probable” wolf kill is when there is physical evidence, but not enough to make it certain so as to clearly confirm the kill.

“Unknown” is used when portions of the carcass wolves usually attack are missing or have deteriorated.

“Not wolf” is the classification used when physical evidence indicates that a wolf did not injure or kill an animal.

The first two categories, “confirmed” and “probable,” are the ones that usually result in payment to a livestock owner by the state or insurance.

Wolf said he sympathizes with livestock owners and understands the process of determining a wolf kill.

“It’s a multistep process that takes longer than it should,” he said. “We’ve tried to streamline it the best we can.”

Nonlethal means

Tuers-Lance emphasized that nonlethal means of protecting livestock from wolves are a critical element of the program and must be used.

She emphasized the importance of removing carcasses, which attract wolves, and said livestock owners should use lights, noise or fladry — the use of brightly colored flags evenly spaced and hung on a wire around a pasture or other area where livestock gather. Wolves are afraid of new things, like fluttering flags. This fear makes them cautious about crossing the fladry boundaries — at least for a few weeks.

Williams also said to keep records and note times you’re in the field with the livestock. That counts as human presence to ward off wolves.

“We still have to work under the wolf plan,” Tuers-Lance said.

But, as Williams said, progress is being made.

“We’re heading in the right direction,” he said. “By letting the local ODFW folks know what’s going on, they can tell their superiors.”