Vaccination rates in Oregon among lowest in the country

Published 7:30 am Thursday, July 19, 2018

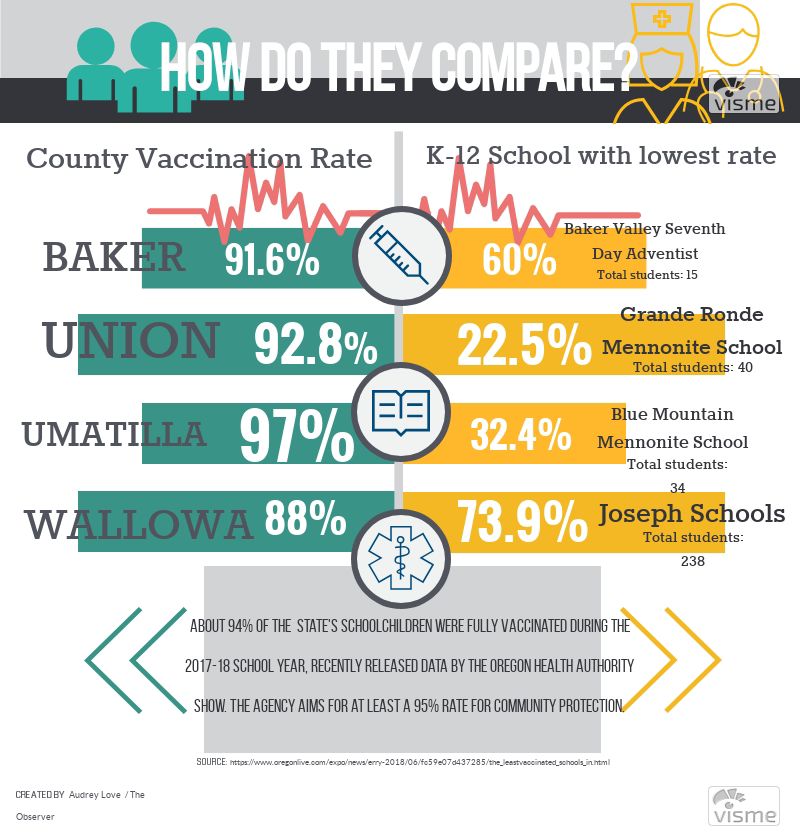

- Illustration by Audrey Love

Oregon has some of the lowest vaccination rates in the country — seventh lowest, to be exact, according to estimates by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

According to the Oregon Health Authority, the state requires that all students attending public, private, charter and alternative elementary, middle and high schools be vaccinated. Shots are also required for attendance at all preschools, certified child care facilities and at Head Start programs. At initial enrollment, children need a signed Certificate of Immunization Status form, which must show at least one dose of each of the following vaccines: diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (whooping cough), mumps, rubella, measles, hepatitis A and B, polio, varicella (chickenpox) and Hib (for children under five years of age). In addition, teachers, administrators and school personnel follow the same vaccination guidelines as students.

At all ages and grades, the number of doses required varies by the child’s age and how long ago they were vaccinated. Children are not allowed to start school or attend child care without these minimum requirements unless they file for a medical or non-medical exemption. The state allows medical exemptions for those who have a medical condition that contraindicates (makes it inadvisable to prescribe a particular drug, procedure or treatment) vaccination, and must be signed by a physician or authorized representative of the local health department. Those seeking a non-medical exemption must obtain a Vaccine Education Certificate by either viewing an education module online or seeing a health care practitioner, essentially proving the parent has been educated on the risks of not vaccinating. While non-medical exemptions are often religious in reasoning, they also fall under a matter of personal philosophy.

“We do have several parents who choose not to vaccinate their children,” said Jessica McKaig, secretary at Heidi Ho Christian Preschool and Kindergarten in La Grande. “Usually it is because they don’t want to expose their kids unnecessarily. Sometimes it is because a parent or relative has had a bad reaction to a vaccine at some point and (they) fear the same for their child.”

However, children with either exemption are, naturally, considered susceptible because they maintain a higher risk of contracting a vaccine-preventable disease.

“If you go out into the public, you’re exposing others to that disease, (including) the ones who are the most vulnerable — youth who haven’t been vaccinated yet, who aren’t old enough, or the elderly or folks’ whose immune systems are compromised (such as those who’ve suffered from cancer),” said Andi Walsh, community relations, grants and emergency preparedness coordinator for the Center for Human Development. “There’s reasons for thinking about the greater good.”

In the case of an outbreak of vaccine-preventable disease in a community, the local health department has the legal authority to exclude from school or child care attendance any child who has not been completely immunized, according to the Oregon Health Authority.

“The last two summers we’ve had outbreaks for vaccine-preventable diseases,” Walsh said. “We had mumps last year and pertussis the year before. Both mumps and pertussis were parts of communities that don’t vaccinate. So when people choose not to vaccinate themselves or their children, they put the community at risk.”

A rise in concern for both the necessity and health risks associated with vaccinations has been at the forefront of discussion and debate in recent years, most notably with claims that vaccines cause autism, contain unsafe toxins, or are no longer needed due to herd immunity or lack of presence.

“All parents want to do the best thing we can for our kids. The majority of parents have the best intentions of what is the safest thing for their children,” Walsh said. “You have the science-based side of vaccines versus another portion of folks who feel that vaccines cause problems to their children, so they choose not to vaccinate because they feel it’s a health issue, (as compared to) what happens if (they) don’t vaccinate.”

An overwhelming majority of these concerns, however, can be debunked. Vaccines, like all medical interventions, have the potential to cause harm. It’s important to note that no vaccine recommended for use has been found to be more harmful than the disease it helps prevent, according to Boost Oregon Vaccination Education, and those that have proven ineffective in the past have been pulled from the market and replaced with safer alternatives.

“Every medication that people take has risks for side effects; however, vaccinations are some of the most tested products on the medical market,” said Elizabeth Sieders, RN, and immunization coordinator and communicable disease investigator for CHD. “Each vaccine undergoes extensive clinical research before they are approved for use, and then continue to be monitored closely. Every vaccine reaction that occurs in the U.S. is documented for the use of studying what potential threats they could pose to humans.”

Another term that frequents vaccination debate and defense of non-vaccination is “herd immunity,” a concept that Sieders said is used to describe when a community of people are vaccinated, or immune to a disease, and therefore provide protection to its members who aren’t vaccinated by limiting the possibility of bringing the disease into their community.

“Some diseases, pertussis for example, which we have had outbreaks of often in Eastern Oregon, requires a 90 to 95 percent vaccination rate in a group of people to protect its most vulnerable populations,” Sieders said. “If children do not get immunized, that herd immunity will be lost. As herd immunity declines and rates of non-vaccinated children increase, diseases that have previously not been seen for many many years will likely return. We saw this with the outbreak of mumps last year in our county. Diseases spread easily in large groups of people who spend extended time together, such as schools, and the more unvaccinated children there are the more potential (there is) for outbreaks to occur.”

Though the presence of vaccine-preventable diseases remains largely unseen in Oregon and the rest of the United States, save for minor outbreaks, it doesn’t mean they have been eradicated. Smallpox is the only infectious disease to have ever been eradicated, according to the World Health Organization, and took decades to accomplish. If the vaccination of a certain disease ceases within a community, that disease is likely to return.

“We have been very fortunate in the U.S. to be able to go generations without seeing crippling disease outbreaks, and because of that I think we, as a general population, do not take the risks of these diseases serious,” Sieders said. “Many of the vaccine-preventable diseases can and do cause death, and because of the incubation period of most viruses it is impossible to just isolate yourself from infected persons. While vaccines are not perfect at creating immunity to diseases, they do increase your chances of not contracting the diseases exponentially.”

“These are scary things,” seconded Walsh, “things people don’t even realize are scary because they haven’t seen them in their lifetime.”

Though it is a parent’s right to exempt their child(ren) from one or more state-required vaccines, both Walsh and Sieders agree that decision should be a highly-informed one.

“What is important for parents to consider is if the risks of vaccination outweigh the risks of contracting a vaccine preventable disease,” Sieders said. “Statistically, the diseases vaccines treat cause much more harm, every year.”

Walsh gives parents this advice: “Be sure to check reliable sources. Get both sides of the picture before you make a decision. Visit with your medical providers and get input from them and think about the consequences down the road. If you choose not to vaccinate, are you willing to take the risk of when your child does contract that disease? Is it worth the risk?”

While the issue of immunization largely focuses on children, adults are also encouraged to be aware of their immunization status and stay up-to-date if they either didn’t receive a vaccination as a child or to receive boosters, as protection may wane under certain conditions such as childbirth, according to Walsh.

For more information concerning vaccination, contact your local health care provider or the Center for Human Development in La Grande, and visit the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website at cdc.gov, the Oregon Health Authority at oregon.gov/oha or boostoregon.org.

Contact Audrey Love at 541-963-3161 or email alove@lagrandeobserver.com.