When basalt (and wildflowers) beckon

Published 7:00 pm Friday, June 9, 2023

- Jacoby

If I am ever kidnapped, blindfolded and then dropped off somewhere between the Anthony Lakes Highway and Ladd Canyon, I’d like to believe I would quickly recognize roughly where I was.

Trending

Assuming it was daylight, anyway.

An unlikely scenario, to be sure.

And one I am not keen to investigate except in theory.

Trending

But I had cause to ponder the matter recently during a hike in the aforementioned section of the Blue Mountains, near the Ladd Canyon Road between Wolf and Beaver creeks.

Anthony Lakes Highway has long seemed to me more than a geographic boundary.

Although the two-lane paved road, which leads from Baker Valley into the Elkhorn Mountains, doesn’t define an immediate and dramatic shift in the landscape, there are notable differences between the two sides.

The most noteworthy, to my eyes, is geologic.

South of the highway and extending for several miles in that direction, the predominant rock is the granitic stock of the Bald Mountain batholith (technically granodiorite due to its mineral and chemical composition, but a close cousin to granite, hence “granitic”). That’s a mass of magma that solidified underground about 145 million years ago. Subsequent uplift, followed by the weathering effects of water, wind and, especially, glacial ice, sculpted the mountains so beloved by skiers, hikers, mountain bikers and photographers.

The granitic rocks extend north of the highway, but for a shorter distance compared to their southern extension, which is why I think of the highway as a divider.

To the north, the batholith is overlain by altogether different and much younger rocks. These are part of the Columbia River flood basalts, one of the largest outpourings of lava flows on Earth. In places the contact between the two disparate formations is sudden, exposed in a single roadcut or outcropping.

The basalts, which continue north and northeast for dozens of miles, make up most of the northern Blue Mountains and cover large areas of Northeastern Oregon and the southeast corner of Washington, as well as western Idaho. The farthest traveled of these lava flows flowed west to the Pacific Ocean. The Columbia River carved its great gorge through multiple layers of those flows.

The granitic rocks and the basalts have one thing in common — both are igneous, meaning they were originally molten.

But their differences are numerous and conspicuous.

Color

Basalt is brown (in various shades, from tan to nearly black). The granitics are grayish white.

Texture

Basalt is smoother, with much smaller crystals, typical of magma that cools relatively rapidly.

Granitic rocks, being underground, cool much more slowly and have larger crystals — easily visible to the naked eye as blotches of black and other colors — and a rougher surface, rather like sandpaper.

Geologic history

Geologists have determined that Columbia River flood basalts, most of which (99%) erupted from about 15 to 17 million years ago, issued from hundreds of vents, mainly in northern Nevada, Eastern Oregon, and Southeastern Washington.

These highly fluid lava flows — think warm honey rather than, say, thick paste — built broad shield volcanoes, covered wide plains, and filled canyons. The immense volume of these lava flows largely overwhelmed the landscape of this part of the Pacific Northwest, thus the term “flood basalts.” Deeply eroded remnants of some Columbia River basalt vents are still visible in the Wallowa Mountains, where stripes of basalt (known as sills and dikes) slash through the much older white granitics and limestones, like lines scrawled by a brown crayon on a sheet of paper.

The granitics of the Bald Mountain batholith, by contrast, didn’t erupt at all. The magma cooled slowly deep beneath the ground and was later exposed by erosion. Geologists call such rocks “intrusive,” to differentiate them from flood basalts and other volcanic, or “extrusive,” formations.

Basalt and granitic rocks also differ in their proportion of silica, a major component of all igneous rocks. Basalt has a relatively low percentage of silica — 45% to 55% by weight — compared with more than 65% for granitic rocks.

Although the basalts in this case are extrusive, and the granitics intrusive, this isn’t always the case.

Basaltic magma can also cool underground, in which case it’s called gabbro. Higher-silica magma that erupts on the surface rather than cooling below ground is known as rhyolite.

Scablands

The difference that distinguishes the two regions for me — and the reason I’m confident I would know where I was, were I the unfortunate victim of that kidnapping scenario — is on the ground, and particularly on or near ridgetops.

To the south, on the granitic batholith, ridges tend to be dominated by boulders interspersed with expanses of sandy soil.

But in the basalt country the landscape is quite different. The exposed rock on ridgelines often is made of smaller, angular blocks rather than rounded boulders, and the soil far more likely to turn to mud during the spring snowmelt or after a summer cloudburst.

The word that comes first to my mind is “scabland.”

This denotes the thin, scant soil, with bedrock at or very near the surface, and few trees. The appearance is vastly different from the granitic mountains, befitting their disaparate geologic histories.

The contrast is so distinct that I am reminded, whenever I visit, how fortunate we are to live so near to the Wallowa-Whitman National Forest, with its great diversity.

As inhospitable as these basalt scablands are, each year the dull brown expanses are briefly but beautifully brightened by a riot of wildflowers.

And it was that show which drew me on the sunny and warm afternoon of Sunday, June 4 along with my wife, Lisa, and our kids, Olivia and Max.

We had business to attend to in La Grande, so my intended route was to drive past Wolf Creek Reservoir to the divide between Wolf and Beaver creeks, then along the Ladd Canyon Road, No. 43, to Interstate 84.

Somewhere in between I wanted to find a place to hike.

I perused an online topographic map and found a likely spot. A series of side roads off Road 43 cross what appeared, by my reckoning of the contour lines, to be something of a plateau on a west-facing exposure. I figured this area would be a prime wildflower spot, particularly given the damp spring.

I chose wisely.

We hadn’t walked but a quarter mile before we reached a place where water was seeping from the basalt and trickling onto the road. A slope, which possibly by July, and almost certainly by August will be dry and brown, was a carpet of bright green grass interspersed with several species of wildflower.

Lisa and I were especially gratified to find one of our mutual favorites — camas.

Although we appreciate the flower for its brilliant purple petals, Native Americans placed a much higher value on the plant, digging to collect its edible roots.

The patch, which extended on both sides of the road, was also rife with the even darker purple of larkspur and the pink-white-yellow-black blooms of shooting stars. On the fringes of the forest the glistening yellow balsamroot was at its brightest.

We continued for two miles, heading generally northwest toward Beaver Creek. The road, being near the crest of the divide, was relatively flat. We passed an elk camp with one of the largest fire rings — constructed, inevitably, of basalt rocks — that I’ve seen.

Based on the map, a hiker could spend a few days in the area without walking every mile of road.

We saw neither elk nor other wildlife, save for birds.

But we also didn’t see another person.

If you’re coming from La Grande or points north, drive Interstate 84 to the Ladd Creek exit. Follow the gravel Ladd Canyon Road, Forest Road 43, for 14 miles to the junction with Road 190, which branches off to the right, and uphill.

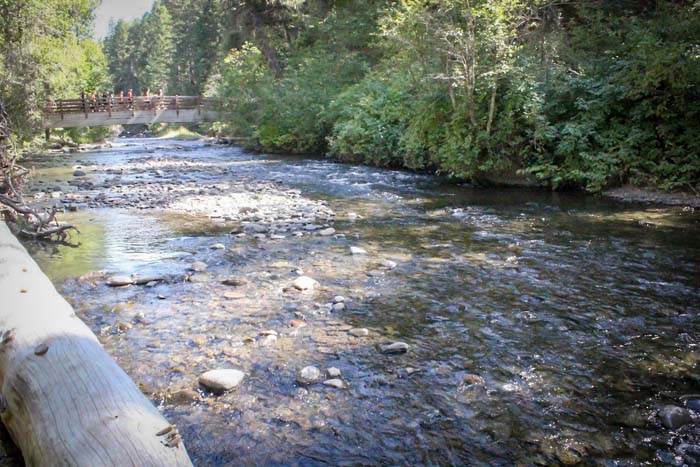

If you’re coming from Baker City, North Powder or points south, drive Interstate 84 to the Wolf Creek exit, a couple miles north of North Powder, and follow Wolf Creek Road to Wolf Creek Reservoir. Continue on the main road along the east side of the reservoir, past a couple cabins, and into the forest. The road becomes Forest Road 4315, and it follows the canyon of the north fork of Wolf Creek. Continue on Road 4315 for about 19 miles (from the reservoir) to a junction with the Ladd Canyon Road, No. 43. Turn right and follow Road 43 for two miles to the junction with Road 190.

Roads 43 and 4315 are both well-maintained gravel roads. Road 4315 is narrower, with steeper grades as it climbs along the canyon wall above the north fork of Wolf Creek.